Commonplace 187 George & Demos (Again) PART TWO.

Oh, dear. The UK Referendum - I am sorry to say the wrong side won, by the barest of majorities. I voted to Remain; it seems the three Rs voted to Leave - that is, the Rich, the Racists and the Reactionaries - leading the way for the Far Right of Europe to step up its game. And for that odious slime mound of self-serving, conniving, unscrupulous egomania that is Boris Johnson to become the next UK Prime Minister. But, as post-French Revolution philosopher Joseph de Maistre once said:

in a democracy, people get the leaders they deserve, so shame on us. On behalf of all sane Brits, European Union: I apologise. And to the up and coming generation of Brits who will suffer - I am ashamed of us, the older generation, who have let you down. A sad, sad, awful result.

Anyhoo, back to George & Demos...

Manor Park Cemetery in Newham, lies midway between the centre of London and Romford in Essex, 7 miles north-east of Charing Cross station. George wrote Demos in 1885/6, so he will have been familiar with the cemetery when it was new and still somewhat under construction. It was and still is, a private enterprise operation run by the family who started it. The cemetery website tells us one of Jack The Ripper's victims (Annie Chapman) is buried there; she died in 1888, the same year as George's first wife, Marianne aka Nell, who lies buried south of the River Thames.

|

| The City of London Cemetery c 1855 |

I am grateful to the E7 Now & Then website

click for this snippet of information: in 1854, the Corporation of the City of London paid

£200,000 for 12 acres of land to build a cemetery on. It opened 2 years later to accommodate 6,000 burials a year. Twenty years later this was developed into the Manor Park Cemetery. According to the website, the project went way over budget because the plan was to make it a pinnacle of beauty and restful repose, complete with decorative architectural features, statuary, well-laid out walks and lush planting.

The area had once been a semi-rural paradise of smallholdings and market gardens serving the needs of Londoners, but it was ripe for development when the nineteenth century economic boom arrived, and the demand for workers required to service such expansion saw the demand soar for accommodation for both the living and the dead. In nearby West Ham, the population increased by 240,000 between 1850-1900, thanks to an influx of immigrants and the development of both the London docks and the railways. In Demos, George likens this development to 'the spreading of a disease' (of course), because he hated new-fangledness and change.

The industrial strength new-build of the area was everything George hated about the state of nineteenth century life. Rows of uniform houses all built to a repetitive configuration for people he considered drones. But wasn't it the ancient Romans and Greeks who liked their urban spaces neat and uniform? Town planning aspires to optimise the usage of space, and all those workers providing the likes of George with the trappings of his aspirational lifestyle had to live somewhere cheap and accessible to the workplace, in homes with comfort and security. But, George preferred those he considered his inferiors to be kept well out of sight, preferably well away from his own back yard, so that he could enjoy country rambles and appreciate its 'verdure' - his over-used archaic term for greenery - on those rare occasions he took himself out for a walk. In fact, houses throughout recorded history have been 'jerry built', by speculators who didn't expect their work to last forever. For every historic building we have a thousand others that have crumbled to rubble, and the new build replacing them welcomed as an improvement. The random nature of the historic parts of towns such as York and London testify to speculative schemes operated by anyone with bricks and mortar and a plot of land to build on. But, for George, such places were emblematic of the End of Days - industrialisation and homogeneity defacing the world forever, necessitated by the rise of the Proletariat with money to burn and no sense of aesthetics.

This much-feared blighting of some mythical Albion features in Demos. The working class hero, Richard Mutimer, sets his sights on building a new town for his, workers complete with factories, spanking new homes and loads of educational and cultural places for them to develop themselves - in contrast to the middle class hero, Mr Eldon, who has plans to return it all to rolling countryside when he gets his hands on his (rightful) inheritance, probably make it into a fox-hunting, pleb-baiting outpost, like all posh people want to when they get their hands on 'land'. There seems to be something mythic about owning ground that feeds into the souls of those who want power: a bricks and mortar house is not enough - it has to be the soil it's built on that satisfies them.

|

| Modern map as found on this interesting website click known as Welcome To Manor Park |

We know from George's shorter novels and some of his short stories that he had a horror of suburbia, which was at odds with the fact he opted to live in places like Epsom which couldn't have been more suburban if it tried. And, it has to be said, George was a suburbanite through and through, because he was unhappy in the centre of London, and in the relative countryside of Exeter. If the vile Henry Ryecroft is a manifestation of George, it is a portrait of the author, not 'at grass', but in his back garden, tending his roses and moaning about the state of his neighbours' greenfly.

The Woodgrange Estate in the Forest Gate area close to Manor Park was one of those suburban developments George so hated, but, it seems his assessment is unfair. According to the local council historical perspective:

The basic designs used on the Estate are

repetitive, but the varied uses of standard details created an interesting

variety while retaining the uniform overall character. These details include

the use of different types of brick, iron front railings and gates and other

ornamental ironwork, stucco and artificial stone decorative features. A

distinctive feature was the glazed canopies to frontages (some of the larger

houses also had canopies and loggias to the rear). These canopies, with their

ornamental iron columns and valences, provided an architectural link to the

railway stations of Forest Gate and Manor Park. Corbett was responsible for

securing new and improved road bridges over the railway, the rebuilding of

Forest Gate Station in the early 1880s and the negotiations with the Great

eastern Railway for special "workmen's" fares from Manor Park

Station. The larger houses to the west had servant's quarters attached,

set back slightly from the main house frontage. Corbett also attempted to

landscape his "villas" by providing traffic islands in Richmond Road

planted with trees and front gardens with hedges and lime trees were also

planted. Added to these, 50 street trees were planted in Balmoral Road. Some of

the shops on Woodgrange Road were also built as part of the development, adding

to the already thriving trade on Woodgrange and Romford Roads. 'Corbett' was Thomas Corbett, a devout Scots land developer and architect of model housing schemes.

|

| Frontage of the estate homes. |

So, we see a clear decision to bring a good quality of life to the area, with consideration of open spaces and well laid out thoroughfares, and the application of ordered principles of design. Shops and the sort of infrastructure all villages require were incorporated into the plans, an ideal setting in which the lower middle class could live and prosper.

And, so to the Manor Park Cemetery of George's Demos. This extract is rightly famed as one of his gems. Demos was written before George morphed into the dark, reactionary snob he became in the 1890s. Imagine what he could have produced if he had managed to retain this light. If you haven't read Demos, get you here

click for a free copy. Notes: Jane Vine is the sister of the badly-treated working class angel heroine Emma, jilted by her fiance, Richard Mutimer, who has taken up with middle class girl, Adela. Jane has died of rheumatic fever brought on by poverty and over-work. A 'foss' is a ditch.

Jane Vine

was buried on Sunday afternoon, her sisters alone accompanying her to the

grave. Alice had with difficulty obtained admission to her mother's room, and

it seemed to her that the news she brought was received with little emotion.

The old woman had an air of dogged weariness; she did not look her daughter in

the face, and spoke only in monosyllables. Her face was yellow, her cheeks like

wrinkled parchment.

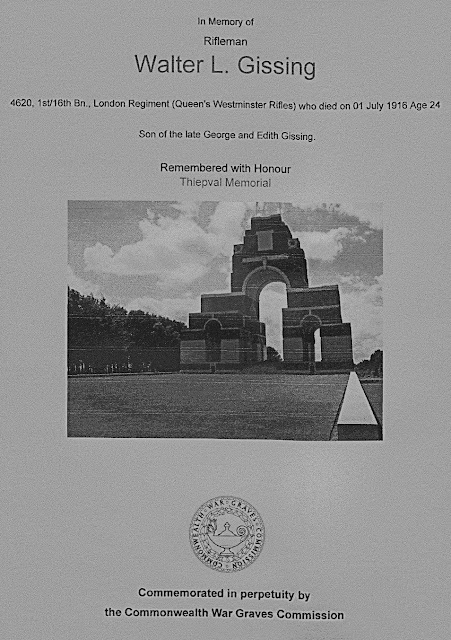

Manor Park Cemetery lies in the

remote East End, and gives sleeping-places to the inhabitants of a vast

district. There Jane's parents lay, not in a grave to themselves, but buried

amidst the nameless dead, in that part of the ground reserved for those who can

purchase no more than a portion in the foss which is filled when its occupants

reach statutable distance from the surface. The regions around were then being

built upon for the first time; the familiar streets of pale, damp brick were

stretching here and there, continuing London, much like the spreading of a

disease. Epping Forest is near at hand, and nearer the dreary expanse of

Wanstead Flats.

Not grief, but chill desolation

makes this cemetery its abode. A country churchyard touches the tenderest memories,

and softens the heart with longing for the eternal rest. The cemeteries of

wealthy London abound in dear and great associations, or at worst preach

homilies which connect themselves with human dignity and pride. Here on the

waste limits of that dread East, to wander among tombs is to go hand in hand

with the stark and eyeless emblem of mortality; the spirit falls beneath the

cold burden of ignoble destiny. Here lie those who were born for toll; who,

when toil has worn them to the uttermost, have but to yield their useless

breath and pass into oblivion. For them is no day, only the brief twilight of a

winter sky between the former and the latter night. For them no aspiration; for

them no hope of memory in the dust; their very children are wearied into

forgetfulness. Indistinguishable units in the vast throng that labours but to

support life, the name of each, father, mother, child, is as a dumb cry for the

warmth and love of which Fate so stinted them. The wind wails above their

narrow tenements; the sandy soil, soaking in the rain as soon as it has fallen,

is a symbol of the great world which absorbs their toil and straightway blots

their being.

It being Sunday afternoon the

number of funerals was considerable; even to bury their dead the toilers cannot

lose a day of the wage week. Around the chapel was a great collection of black

vehicles with sham-tailed mortuary horses; several of the families present must

have left themselves bare in order to clothe a coffin in the way they deemed

seemly. Emma and her sister had made their own funeral garments, and the

former, in consenting for the sake of poor Jane to receive the aid which

Mutimer offered, had insisted through Alice that there should be no expenditure

beyond the strictly needful. The carriage which conveyed her and Kate alone

followed the hearse from Hoxton; it rattled along at a merry pace, for the way

was lengthy, and a bitter wind urged men and horses to speed. The occupants of

the box kept up a jesting colloquy.

Impossible to read the burial service

over each of the dead separately; time would not allow it. Emma and Kate found

themselves crowded among a number of sobbing women, just in time to seat

themselves before the service began. Neither of them had moist eyes; the elder

looked about the chapel with blank gaze, often shivering with cold; Emma's face

was bent downwards, deadly pale, set in unchanging woe. A world had fallen to

pieces about her; she did not feel the ground upon which she trod; there seemed

no way from amid the ruins. She had no strong religious faith; a wail in the

darkness was all the expression her heart could attain to; in the present

anguish she could not turn her thoughts to that far vision of a life hereafter.

All day she had striven to realise that a box of wood contained all that was

left of her sister. The voice of the clergyman struck her ear with meaningless

monotony. Not immortality did she ask for, but one more whisper from the lips

that could not speak, one throb of the heart she had striven so despairingly to

warm against her own.

Kate was plucking at her arm, for

the service was over, and unconsciously she was impeding people who wished to

pass from the seats. With difficulty she rose and walked; the cold seemed to

have checked the flow of her blood; she noticed the breath rising from her

mouth, and wondered that she could have so much whilst those dear lips were

breathless. Then she was being led over hard snow, towards a place where men

stood, where there was new-turned earth, where a coffin lay upon the ground. She

suffered the sound of more words which she could not follow, then heard the

dull falling of clods upon hollow wood. A hand seemed to clutch her throat, she

struggled convulsively and cried aloud. But the tears would not come.

No memory of the return home dwelt

afterwards in her mind. The white earth, the headstones sprinkled with snow,

the vast grey sky over which darkness was already creeping, the wind and the

clergyman's voice joining in woeful chant, these alone remained with her to mark

the day. Between it and the days which then commenced lay formless void.