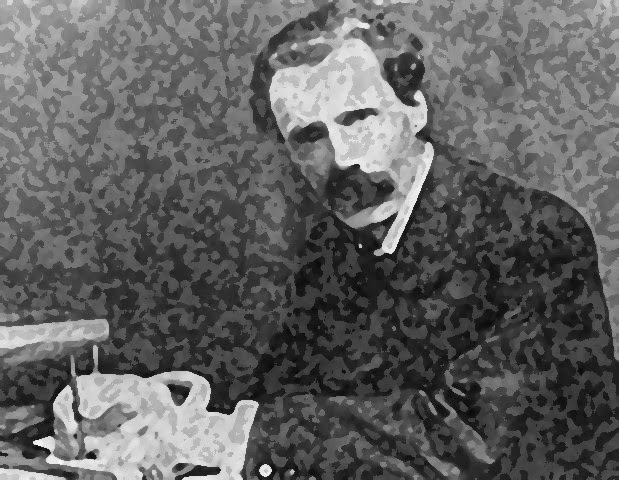

Commonplace 112 George & 'The Wheels of Chance: A Bicycling Idyll'

Possibly the only humorous anecdote ever

told about George was the one where HG Wells taught him to ride a bike.

Admittedly, it was more of a sight gag (in the style of the Keystone Cops!) and

was probably funnier to see than to hear about, but it mentions George laughing

uncontrollably, rolling round the floor with mirth, and so becomes a thing

worth noting - a bit like rocking horse poop and hens' teeth. This was July 3rd 1898. HG was not afraid

to take the mickey out of George - and if more folk had bothered to do that (to

his face haha) then we might not have had to wade through Veranilda. Anyhoo, in

his (mildly) amusing novel 'The Wheels of Chance', HG makes a reference to

George in slightly piss-taking less than reverential tones, and so that is also

worth noting.

HG Wells was always a big fan of cycling.

Did he take up the habit when he worked as an apprentice in the King's Emporium

in Southsea? Portsmouth (Southsea is in Portsmouth) is one of the flattest

places there is in England - in HG's time (as now), the steepest bits would

have been the roads over the railway lines at what was called Somers Road

Bridge and Fratton Bridge, and neither would present much of a problem to a

cyclist because the main railway line is built in the excavations of the old

canal system, and so are well below the road levels. Both are within easy reach

of King's Road, where HG's store was then sited. The bicycle is almost queen in

Southsea - here is a snap of the Portsmouth Annual Nude Cycle Ride click held in early summer,

when the brave set out to amuse and delight

HG's dedication to the two-wheel world went as far as to get the famous company Humber to design a tandem

for himself and his wife Jane, where he would ride in the rear, and take

control of the steering with special mid-section mounted handlebars - money

being no object, obviously. And we will not make a Freudian analysis of it. At the end of his first ever extended cycling tour

with Jane HG proposed to her and she accepted.

'The Wheels of Chance: A Bicycling Idyll' was written in Woking, in a

small house with so little space HG had to use the dining room as a study. In this

small room, he wrote this light piece, plus the The War of the Worlds, and the Invisible

Man, all within earshot of the main railways trundling past.

So, we find the male protagonist, Hoopdriver, setting off for his life-changing trip, a bicycle novice, wobbly and unsure of himself, a mere beginner in the great bike ride of life. Wheels starts with this: Literature

is revelation. Modern literature in indecorous revelation.

Indecorous because it deals with 1) the emancipated art of cycling; 2) it

concerns a single man and a single woman, unchaperoned meeting up and enjoying

each other's company; 3) it crosses class barriers; 4) it shows a humble chap, in trying to rail against his class and place in the scheme of things, abandoning, albeit temporarily, his moral compass.

Hoopdriver sets off on his annual holiday, bicycling the English

South: Esher, Ringwood, Blandford, Midhurst, Guildford, and bits of the The New Forest where the Rufus Stone click reminds we Brits that royalty is expendable. And Portsmouth - almost to the King’s Road Southsea Emporium

where Wells had worked as a drapery apprentice himself.

He meets a Young Lady in Grey (not a Woman in White - the book name-drops popular authors and literary references all the way) who turns out to be a bicycling expert, and something of a ‘New Woman’ determined to live life her way - and that means with few social constraints and financially independent of her family. She outrides him, cocks a snook at convention and renders him smitten, mainly because she initially seems so far above him and out of reach (she rides faster and he has to work to catch her). They team up, and set off together. But Hoopdriver is ashamed of his origins, and adopts a fake persona (a wealthy South African diamond mining, lion-wrestling man's man) in order to appear to be a better social prospect. He mangles the English language with his pronunciation, but as this could also be an attempt to render the character's native London-ish sound, it is difficult to work out if you, the reader, are meant to hear that distinctive South African twang.

He meets a Young Lady in Grey (not a Woman in White - the book name-drops popular authors and literary references all the way) who turns out to be a bicycling expert, and something of a ‘New Woman’ determined to live life her way - and that means with few social constraints and financially independent of her family. She outrides him, cocks a snook at convention and renders him smitten, mainly because she initially seems so far above him and out of reach (she rides faster and he has to work to catch her). They team up, and set off together. But Hoopdriver is ashamed of his origins, and adopts a fake persona (a wealthy South African diamond mining, lion-wrestling man's man) in order to appear to be a better social prospect. He mangles the English language with his pronunciation, but as this could also be an attempt to render the character's native London-ish sound, it is difficult to work out if you, the reader, are meant to hear that distinctive South African twang.

Now, I'm not accusing HG of plagiarism, but the novel is a sort of light-hearted Born in Exile - trust me, the two

novels share some basic themes. It is not at all 'serious' in any of them, as it was probably intended for the sort of readership that would not have found a home between George's densely-packed, existentially wrought pages, and so is intended to appeal to the library member or Mudie's devotee click. Wells makes light of the disastrous situation - maybe George's 'Our Friend The Charlatan' learnt something from Wells' treatment of moral dilemma meets social opportunism in the name of shifting units off the shop shelf? And, in regard to the likes of Mudie's strict 'Hays Code', Wheels plays it very safe.

Here is Hoopdriver, ashamed of his humble beginnings as a drapery store assistant, forced to think about the moral implications of making up unbelievable stories to win a girl from a slightly higher class:

Here is Hoopdriver, ashamed of his humble beginnings as a drapery store assistant, forced to think about the moral implications of making up unbelievable stories to win a girl from a slightly higher class:

At first Jessie had been only an impressionistic

sketch upon his mind, something feminine, active, and dazzling, something

emphatically ‘above’ him, cast into his company by a kindly fate. His chief

idea, at the outset... had been to live up to her level, by pretending to

be more exceptional, more wealthy, better educated, and, above all, better born

than he was.

It is at the start of Chapter 10 that George is mentioned: Hoopdriver is pondering his place in the system of things and the injustice of being trapped in a lowly job that he hates:

Mr Hoopdriver was (in the days of this story) a

poet, though he had never written a line of verse. Or perhaps romancer will

describe him better. Like I know not how many of those who do the fetching and

carrying of life, - a great number of them certainly, - his real life was

absolutely uninteresting, and if he had faced it as realistically as such

people do in Mr. Gissing’s novels, he would probably have come by way of drink

to suicide in the course of a year. On the contrary, he was always decorating

his existence with imaginative tags, hopes, and poses, deliberate and yet quite

effectual self-deceptions; his experiences were mere material for a romantic

superstructure. In reality, and in a nutshell, this contrasts the essential character and personality differences between George and HG - HG the one to not over-think a situation, and George, his own worst enemy.

Hoopdriver, intent on impressing Jessie, attempts to portray his version of a socially, and therefore, sexually, emancipated sort of noble savage, primal, untamed, feral - as befits one raised in the Colonies. He claims to

have wrestled with lions, ridden giraffes and been a diamond miner. This is for comic effect as it stands in stark contrast to the weedy, mediocre, ineffectual character of an apprentice drapery assistant. Then, in more Godwin Peak mode:

They rode on to Cosham and lunched lightly but expensively there… Then the green height of Portsdown Hill tempted them, and leaving their machines in the village they clambered up the slope to the silent red-brick fort that crowned it. Thence they had a view of Portsmouth and its cluster of sister towns, the crowded narrows of the harbour, the Solent and the Isle of Wight like a blue cloud through the hot haze… Mr Hoopdriver… smoked a Red Herring cigarette, and lazily regarded the fortified towns that spread like a map away there…then the beginnings of Landport suburb and the smoky cluster of multitudinous house (one of these Charles Dickens’ birthplace). To the right…the town of Porchester (sic - Portchester is correct) rose among the trees.

|

| Fort Widley, the closest Portsdown Anti-Napoleonic Fort to Cosham. click |

He discussed church-going in a liberal spirit.

‘It’s jest a habit.’ he

said, ‘jest a custom. I don’t see what good it does you at all, really.’

It seems Jessie is a fledgling writer and disciple of Miss Olive Schreiner click which is an arch way of mocking her free spirit nature as a 'Modern Woman', as Ms Schreiner was known for writing books about women who broke boundaries - she was a friend of Edward Carpenter's (see Commonplace 8 for more on Carpenter - and Eduard Bertz, George's other bicycling fanatic friend). But the narrator's/HG's chauvinism shines through: There are no graver or more solemn women in the world than these clever girls whose scholastic advancement has retarded their feminine coquetry.

It seems Jessie is a fledgling writer and disciple of Miss Olive Schreiner click which is an arch way of mocking her free spirit nature as a 'Modern Woman', as Ms Schreiner was known for writing books about women who broke boundaries - she was a friend of Edward Carpenter's (see Commonplace 8 for more on Carpenter - and Eduard Bertz, George's other bicycling fanatic friend). But the narrator's/HG's chauvinism shines through: There are no graver or more solemn women in the world than these clever girls whose scholastic advancement has retarded their feminine coquetry.

Of course, keeping up this act becomes unworkable and futile - Hoopdriver begins to find it a strain to keep up his pretence (much as George and Godwin did), and, again in Godwin mode:

On Sunday night, for no conceivable reason, an

unwonted wakefulness came upon him. Unaccountably he realised he was

a contemptible liar.

In the end, just like Exile's Godwin Peak, he owns up to his humble

origins.

‘Miss Milton - I’m a liar.’ He put his head on one

side and regarded her with a frown of tremendous resolution. Then in measured

accents, and moving his head slowly from side to side, he announced, ‘Ay’m a

deraper.’

‘You’re a draper? I thought –'

‘You thought wrong. But it’s bound to come up. Pins,

attitude, habits – It’s plain enough… I wanted somehow to seem more than I was…

I suppose it’s snobbishness and all that kind of thing…’

And, like Exile’s Sidwell Warricombe, Jessie tells him she would not judge him by his class, but by his innate good qualities.

And, like Exile’s Sidwell Warricombe, Jessie tells him she would not judge him by his class, but by his innate good qualities.

‘Hundreds of men,’ she said, ‘have come from the

very lowest ranks of life. There was Burns, a ploughman; and Hugh Miller, a

stonemason; Dodsley was a footman –.’ As a further prompt, she asks him if he has read ‘Hearts

Insurgent’ – which is the subtitle of Hardy’s ‘Jude the Obscure’. The cruel harshness of Jude's fate seems lost on Jessie, thus rendering her a poseur at education for not realising it.

No, he is not a serious reader, and Jude's trials are unknown to him but he has

dipped into Besant, Ouida, Rider Haggard, Marie

Corelli... ‘a lot of Mrs Braddon’s’. This is HG showing us his hero's so-called low brow tastes; referencing Mrs Braddon is intended to give the reader a deeper insight into Hoopdriver's sexual nature. Mrs Braddon's most celebrated novel is 'Lady Audley's Secret' click, a tale so charged with repressed, suppressed sex it should have had (for its time) an 18 or X rating. To read it was to transgress several moral boundaries and would give Jessie a sign he was a thrilling, daring and adventurous prospect, and a man not afraid to flaunt convention. Just what she was looking for, in fact. And, just to underline his modern man credentials, he is a cigarette smoker, not one of the fusty pipe-smoking or posh cigar-puffing sorts. Cigarettes were then a fashion statement of the bold and the brave, indicative of fearless individualism. And they have been marketed as that ever since. Incidentally, those Red Herring cigarettes are the same brand as used by Dr Watson... elementary, of course. (Wells knew Conan Doyle as a friend and they both had a Portsmouth connection.)

But, Jessie - altogether better educated, better read, better bred - asks him if he only reads novels, and he tells her how woefully he has been educated, and how that is another area of shame. And how unhappy he is being a lowly draper - which is monumentally dreary as well as damned hard work. So she challenges him to rise to his potential, put in the work on his education (via night-classes and lectures, and books she can recommend), and then he can catch up. Here, we can see life is like a bike ride - you just have to pedal harder if you have set off on an inferior machine, but you can catch up and maybe overtake those lucky enough to afford a good quality cycle. But Hoopdriver is not rising to the challenge material yet.

But, Jessie - altogether better educated, better read, better bred - asks him if he only reads novels, and he tells her how woefully he has been educated, and how that is another area of shame. And how unhappy he is being a lowly draper - which is monumentally dreary as well as damned hard work. So she challenges him to rise to his potential, put in the work on his education (via night-classes and lectures, and books she can recommend), and then he can catch up. Here, we can see life is like a bike ride - you just have to pedal harder if you have set off on an inferior machine, but you can catch up and maybe overtake those lucky enough to afford a good quality cycle. But Hoopdriver is not rising to the challenge material yet.

How does it end? Well, he doesn't do himself in, Godwin Peak style. And he

doesn't get the girl - well, not straight away. Jessie, through a cunning plan set in place by her relatives, is forced back to the fold (women can't break out as freedom fighters yet!). She gives him six years in

which to educate and better himself, they part and he goes back to work and the routine of his life takes over once more. It looks like the holiday will be relegated to a series of anecdotes he can tell his apprentice colleagues. But, the seeds have been sown... Jessie has promised to send him books... might he get back on his bike and start the uphill climb - this man who has done the long stretch past the Devil's Punchbowl at Hindhead click, or negotiated the South Downs click, or climbed Box Hill click and breasted Portsdown Hill click in pursuit of his True Love - might he use this exceptional drive to succeed in Life's cycle ride??? Reader, did she marry him?? What are the chances of that??

For a free copy of The Wheels of Chance click

For a free copy of The Wheels of Chance click