Commonplace 107 George & The Honeymoon. PART ONE

If anyone ever argues that George was neither a misogynist nor a Sadist, direct them to The Honeymoon, one of his most repulsive, dislikeable (in a very tough field!), nasty short stories. Wakefield's very own Guy de Maupassant strikes again!

It was written in late 1893 when George was married to Edith, and son Walter was about two years old. They were living in Brixton, and George was making heavy going of it all, as usual. He was deeply unhappy (nothing new, there!), but had the advantage of having something specific to be unhappy about - his home life, he reports in his Diaries, is boring drudgery heaped on misery. Now, in the average Jane or Joe Schmoe, if happiness continued to be as elusive as it was for George, we would take stock and explore a range of options, including assuming some personal responsibility for our own existential self-pity/self-loathing and the stopping of blaming others for our predicament. We would then divert our energies into 'getting a life'. But, that would require a quality of self-awareness, nay, modesty - the sort that allows the possibility we are not always right all of the time. George so often lacked this sort of useful personal attribute. Anyway, he was miserable, though he records (in June 1893, just before the move to Brixton) his bank balance was £116-4-9d. In today's equivalent terms, that would be income for work done of £11K if you check here click (which is good enough of a research tool for Kate Summerscale in her excellent 'The Suspicions of Mr Whicher' published in 2008).

What sort of a honeymoon had he given Edith? Absolutely none - she was shipped down to Devon like so much human cargo, then dragged round the lanes of Redhills and Alphington and Exwick. If she was lucky, she would have been introduced to Pocombe Bridge (!). As with the Brixton residence, George had found a house for them, chosen the fittings and furnishings and it was a done deal when she arrived - did he ever stop and wonder if a woman would actually prefer this? Who doesn't enjoy organising her own home full of things chosen with her partner because they both like them? No, George was too much a control freak power-crazed patriarch to let a wife think she was in a position to make those sorts of decisions. After all, they were his books, not hers, and he was the one with the right sort of 'taste', wasn't he? Hadn't Mrs Gaussen taught him how to spot an acceptable cushion when he was looking at one? haha.

As it happened, George played a blinder when he found poor, hapless Edith, a woman so unlike him in temperament that it would guarantee she would qualify to be his scapegoat for a good few years to come. She was doomed to annoy, irritate, embarrass (in his snobbish eyes) and generally out-moan him and the lengths he went to in order to overpower her would have seen off a lesser woman - it's a tribute to the fortitude of her social background that she held out for so long. If it wasn't for the working classes manning and woman-ing the barricades over millennia, this great British nation would have gone to the wall long ago.

Her perceived failings became his excuse for cruelty and unreasonable behaviour, and this lack of humanity would eventually lead to him abandoning her, and their two children. How she didn't slip something in his cocoa, is beyond my ken - I would have! A phrase he used when writing to the odious Miss Collet about her: 'If only she would accept which side of her bread is buttered'. He spent years ramming that home to poor Edith, after years of ramming that home to poor Marianne aka Nell.

|

| The Honeymoon by Carl Thomsen 1893 Does she know her place yet? |

What sort of a honeymoon had he given Edith? Absolutely none - she was shipped down to Devon like so much human cargo, then dragged round the lanes of Redhills and Alphington and Exwick. If she was lucky, she would have been introduced to Pocombe Bridge (!). As with the Brixton residence, George had found a house for them, chosen the fittings and furnishings and it was a done deal when she arrived - did he ever stop and wonder if a woman would actually prefer this? Who doesn't enjoy organising her own home full of things chosen with her partner because they both like them? No, George was too much a control freak power-crazed patriarch to let a wife think she was in a position to make those sorts of decisions. After all, they were his books, not hers, and he was the one with the right sort of 'taste', wasn't he? Hadn't Mrs Gaussen taught him how to spot an acceptable cushion when he was looking at one? haha.

As it happened, George played a blinder when he found poor, hapless Edith, a woman so unlike him in temperament that it would guarantee she would qualify to be his scapegoat for a good few years to come. She was doomed to annoy, irritate, embarrass (in his snobbish eyes) and generally out-moan him and the lengths he went to in order to overpower her would have seen off a lesser woman - it's a tribute to the fortitude of her social background that she held out for so long. If it wasn't for the working classes manning and woman-ing the barricades over millennia, this great British nation would have gone to the wall long ago.

Her perceived failings became his excuse for cruelty and unreasonable behaviour, and this lack of humanity would eventually lead to him abandoning her, and their two children. How she didn't slip something in his cocoa, is beyond my ken - I would have! A phrase he used when writing to the odious Miss Collet about her: 'If only she would accept which side of her bread is buttered'. He spent years ramming that home to poor Edith, after years of ramming that home to poor Marianne aka Nell.

If living with his first wife Marianne might have taught him anything, it should have been that he was not the marrying kind. But, in her, he had grown used to having a scapegoat and so when he was single once more, he missed having a whipping post on which to vent his resentment and anger at the world that ignored his talents. By living alone, he had no-one to blame for his lack of literary success, no-one to lord it over. There was also the subject of his sex needs - the lack of it drove him out of his mind at times, and he wasn't afraid to tell people about it. He called it 'loneliness' but that was a euphemism for sexual frustration.

He had tried to manoeuvre Edith into living in sin with him, but she was having none of that - and why should she? Her personal morality aside, if she had followed that path, she could lay claim to no legal rights over him, and her children would have been illegitimate at a time when that was considered a blight on one's life - for mother and child. George tried going without sex but that drove him mad; HG Wells thought all his personality problems stemmed from his attitudes to sex - or, more accurately, the place it played in George's mental make-up - and the lack of girl action made him twisted. (Sex was something HG knew something about!) He suggested George couldn't afford to pay for sex, which is not strictly true (maybe he meant he couldn't afford to set up a mistress in a

And, so to the story...

The title is a tease. As with title of The Foolish Virgin, it attempts to titillate the reader (probably male readers - women are more sophisticated!) into thinking it is going to be a little bit saucy. It is - if you get turned on by men degrading women psychologically and then crushing the hopes and dreams out of them. And we know some of you men are built that way. Phyllis is the name of the woman on the honeymoon - the name means 'foliage' and is not to be confused with Sy-phyllis - but, as Freud said, 'There is no such thing as an accident' haha. She is a character from Greek legend who, suffering a broken heart at the non-return from a voyage of her man, Demophoon; she decides to hang herself. She is turned into a nut tree just as he comes back. So, we can assume Phyllis is doomed at the hands of an unreliable man.

The Honeymoon is so full of dislike for women, it should come with a health warning. So, what's is all about? Direct quotes from text in blue.

Phyllis had been reading Swinburne; she dreamt of green seas roaring upon cliffs of granite - ideal music for the commencement of a wedded life which she was determined should at all hazards avoid

the humdrum, the vulgar, and exhibit a union of soul preserving their vital freedom.

Here, George is being cruelly ironic - making use of Swinburne's Romantic allusions to mock her romantic idealism. Then we have the usage of the term 'should at all hazards' - which is a phrase not in common parlance in the UK even in George's time, but evokes the words of Samuel Adams and the Boston Tea Party - 'The liberties of our Country, the freedom of our civil constitution are worth defending at all hazards: And it is our duty to defend them against all attack'. Here, he mocks her idealism and hopes for the marriage. We are being warned Phyllis is in for a mighty shock when she is smashed against the granite cliff of her husband.

George initially refers to him by his surname, which in George's time, and in his adopted class, was the public school habit of referring to men, in particular, by their family name. It also is intended to contrast him with Phyllis - by using her first name, she is diminished and treated as a 'girl' as opposed to her finance's 'man' status. He is ten years older than her twenty three years. He is a journalist by trade. She is wealthy merchant’s daughter, chosen by him for the beauty of her family fortune.

She challenges his change of mind – she reminds him he seemed to have previously supported it, but he says I pretended no such thing. I was most careful not to commit myself. He tells her he decided delay bringing up the subject of abandoning the book until after their wedding. She tells him:

|

| The Waning Honeymoon by George Henry Boughton 1878 The open gate is a clue to her thoughts. |

pied-à-terre), and does not fully realise the place of the 'doormat wife he could wipe his feet on' nature of what George wanted from a relationship with a woman. Imagine George's shock at finding Gabrielle's mother more or less in charge of him when he decamped to France! All that fighting over food and inadequate French breakfasts was really a power struggle she won. Poor St. George, vanquished in the end by un dragon françoise haha.

|

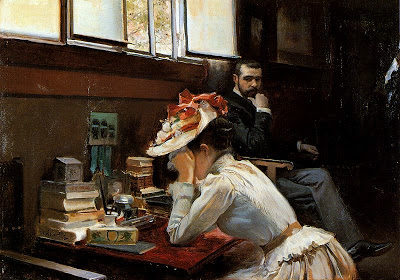

| The Honeymoon by Cecilio Pla ?1890 Her posture says it all: poor girl. |

The title is a tease. As with title of The Foolish Virgin, it attempts to titillate the reader (probably male readers - women are more sophisticated!) into thinking it is going to be a little bit saucy. It is - if you get turned on by men degrading women psychologically and then crushing the hopes and dreams out of them. And we know some of you men are built that way. Phyllis is the name of the woman on the honeymoon - the name means 'foliage' and is not to be confused with Sy-phyllis - but, as Freud said, 'There is no such thing as an accident' haha. She is a character from Greek legend who, suffering a broken heart at the non-return from a voyage of her man, Demophoon; she decides to hang herself. She is turned into a nut tree just as he comes back. So, we can assume Phyllis is doomed at the hands of an unreliable man.

|

| Phyllis and Demophoon by Sir Edward Burne-Jones 1870 |

the humdrum, the vulgar, and exhibit a union of soul preserving their vital freedom.

Here, George is being cruelly ironic - making use of Swinburne's Romantic allusions to mock her romantic idealism. Then we have the usage of the term 'should at all hazards' - which is a phrase not in common parlance in the UK even in George's time, but evokes the words of Samuel Adams and the Boston Tea Party - 'The liberties of our Country, the freedom of our civil constitution are worth defending at all hazards: And it is our duty to defend them against all attack'. Here, he mocks her idealism and hopes for the marriage. We are being warned Phyllis is in for a mighty shock when she is smashed against the granite cliff of her husband.

George initially refers to him by his surname, which in George's time, and in his adopted class, was the public school habit of referring to men, in particular, by their family name. It also is intended to contrast him with Phyllis - by using her first name, she is diminished and treated as a 'girl' as opposed to her finance's 'man' status. He is ten years older than her twenty three years. He is a journalist by trade. She is wealthy merchant’s daughter, chosen by him for the beauty of her family fortune.

Waldron is a devious schemer who pretends to be agreeable and accepting of her traits and personal characteristics, but is biding his time for her to be legally bound to him before he reverts to his real self, and he can assert his true nature over hers. She thinks she knows him by his

journalism – she has read his opinions on various contentious matters

and thinks he might have the talent to be a political prospect. He is a tad wishy washy on the fine details, but she applies her wonky analysis to his affection for her, and dons the infamous rose-tinted glasses. In short, she totally underestimates this piece of work. He had met a girl with money, a girl who fell in love with him, a pretty and healthy and – as things go – not ill-educated girl. Her companionship gave him no little pleasure; there was every likelihood that in future she would worthily play her part as his wife.

Phyllis has written a novel. Waldron initially labelled it ‘charming’, but he admits he is not a lover of fiction (not your typical journo then haha). He makes

little jokes about her work, but she misreads this as affection and his lack of any sort of feedback as approval. (Women are our own worst enemies at times - we try and see the good in all.) She asks him to read the proofs, and has arranged for the last of these to be sent to her as ‘Mrs

Phyllis Waldron’ to arrive on their honeymoon. (Forget that this is a bit far-fetched - it is the sort of thing George would have done himself, so we go with it.) These arrive in the second week of the honeymoon; Phyllis invites his approval of her work and asks him to take a look at the proofs. He nodded and blew a great cloud from under his moustache, but keeps schtum to control the situation, letting her stew in her juices.

|

| King Rene's Honeymoon by Edward Burne-Jones 1864 |

Waldron has avoided marriage up to the point he found a woman with money. He dreaded the

thought of matrimony which means an intensified struggle for bare livelihood.

He is a man who relishes the trappings of a middle class existence, who dreads

the thought of having to live in humble circumstances in a mediocre suburban environment. He did not expect much of Phyllis – he thinks of her as a mere girl

with no depth of character. Phyllis had a great deal to learn, and a younger

man might, perchance, find obstacles in the way of tutorial activity – George’s

creepy, snide way of saying a younger man might fall in love with her for what she is and not what she could be forced to be.

She reminds him about taking a look at her MS. When he looks at it he fails to give any feedback, telling her he will give his opinion the next day, following some

discussion about it he intends to have with her on an afternoon walk he suggests they take. She realises this

is stalling – she had wanted to send it off to be published by return. He asks for the publication date - she initially tells him it should be in two weeks,

then admits there is no certain date. Waldron exploits this and makes her wait. Phyllis is looking forward to

telling all her friends she is a published author, and to feeling approval from her

peer group. Not an unreasonable ambition for a writer!

Waldron keeps her waiting all afternoon for their chat,

never mentioning the book, even though he knows – and is relishing it! – her

anticipation and the anxious mood she is feeling - she is desperate for his opinion. As

he prevaricates, Phyllis becomes subdued, but Waldron is carefully

laying an emotional trap for her to fall into, Sadist that he is.

On their afternoon walk, he finally gets round to it,

but comes across as a totally changed man. No longer using a pet name he has for her, and

speaking in a harsh tone, he refers to her work as this fiction of yours… It

won’t do at all. The book mustn't be published. You will dedommager the

publishers, and there’s an end to it (this means repay the costs so far accrued).

She responds to him as ‘Charley’ (his first name used for the first time) displaying alarm at this change of tone - This

was not her husband. The transformation frightened her. She expresses this,

and Charley responds: An escapade of this sort would shame us.

I have a serious career before me, and can’t afford to be made ridiculous. The

novel is as good as five thousand others that will see the light this year, but

it isn't the kind of thing that you must have anything to do with.

She challenges his change of mind – she reminds him he seemed to have previously supported it, but he says I pretended no such thing. I was most careful not to commit myself. He tells her he decided delay bringing up the subject of abandoning the book until after their wedding. She tells him:

'You amaze me. What am I to think?'

'Well, I foresaw how much easier such little discussions

would be after we had become man and wife. It wasn't worthwhile before.'

'I never thought thought to say such a thing, but – were you afraid

that to tell me the truth might – cause you to lose me?'

The implication here could not be disregarded. Waldron

looked steadily into his wife’s face, and saw how it was changed by anger.

A spirit of resistance had awoken in her, and she would

not spare to use dangerous weapons.

JOIN ME IN PART TWO TO SEE HOW THAT PANS OUT FOR PHYLLIS.

No comments:

Post a Comment