Commonplace 27 George & His First Born, Walter.

In honour of Walter's Birthday on December 10th. Not a biography but notes on his brief, heroic life.

|

| Happy Birthday, Old Sport. |

'Thursday's child has far to go', says the rhyme. George wrote in his diary on Thursday, December 10th 1891: 'So, the poor girl's misery is over and she has what she earnestly desired.' Which means one can assume Walter Leonard came into the world very much wanted by his mother. What were his father's thoughts? A planned pregnancy or a contraceptive malfunction? A means to keep Edith occupied and out of his hair?

|

| Mother and Child by Pablo Picasso 1921 |

By December 30th, George has moaned on for twenty days (with the exception of December 27th: 'Baby quiet, seldom troublesome') and writes in the diary: 'A day of misery, once more, and bitter repentance.' For the marriage - which he forced on Edith when she was back-pedalling and disaster could have been avoided? Or, the birth of his son? George and Edith had been married for just 10 months. Was it an omen they married on what would have been Marianne aka Nell's 33rd birthday?

|

| Greek Boy With Duck. Possibly a depiction of a sick child needing divine intervention holding an animal about to be sacrificed to the gods. |

|

| Iseppo da Porto and His Son Adriano by Veronese c 1580 |

What can have possessed him to commit this thought to paper and posterity? Did he not think either Walter or Alfred would read it at some time, when they trawled through their father's writings?

Whatever George amounted to as an artist, it is hard to excuse his treatment of human beings - especially those nearest and dearest to him - his wives and children.

Walter was first a disappointment, then a challenge, then little more than a burden to his father. The baby's mother seems to have failed to bond with him (a situation more common than you might think), and George tells us she beat him. I suspect her failure to feel much motherly love, initially, was a combination of post-partum depression (after a labour and birth of traumatic suffering) and that the infant Walter was sickly possibly with a mild form of scrofula, the TB his father suffered from and failed to tell his mother about. Walter was blemished with a large mole, had a severe rash that made him tetchy and kept him awake, and breast-feeding was too painful for the already ailing mother to endure. Many women have problems with breast-feeding, and often the cycle of pain, disappointment and anger corrode the mother-child bond. George would not be much use to her, being lacking in sympathy (though even he acknowledges the suffering she endured during the birth) and hugely disappointed that the fruit of his loins was such a horror - he reports neighbours being shocked at Walter's appearance when he pushed the baby in his pram.

No doubt Darwin was speaking in George's ear and hinting at some blight to the bloodline of the child's mother - after all, 'aristocratic' fathers do not beget defective offspring, do they? No doubt Edith sensed (or was told) this at some stage. And, let's be clear: Edith was living with a passive-aggressive tyrant who no doubt belittled her at every turn, a weak man who disabled her in life with his patronising and critical character and who failed to do more than honour the basics in the marriage. In a previous blog I mentioned all he required of her was an ability to manage servants and own a vagina. Well, she couldn't do servants, and then this freak of Nature pops out of her vagina... When did George start to think about getting rid of her? I suspect long before Walter arrived.

|

| Portrait of Alexander Cassatt and His Son, Robert Kelso Cassatt by Mary Cassatt 1884 |

(Literally) farming out his children was a regular pattern for George who was to exercise this 'Get Out of Jail' card whenever it suited him. However, let us not dwell on George's lack of fatherly-feeling - after all, didn't he take more after his mother than his father? Substitute her religion for his conservatism, and you begin to see his character was much more like hers. Think about it!

Again, what possessed George to write in his diary (written whilst the family of four was on holiday in Mablethorpe) on August 9th 1896: 'What a terrible lesson is the existence of this child, born of a loveless and utterly unsuitable marriage?' (And, still, some call George 'heroic'? The whole entry is a terrible stew of offensive remarks about his boy.) 'Nothing could be more difficult than my position as regards the boy Walter. All but every statement made to him he answers with a blunt contradiction; to all but every bidding he replies, 'I shan't'. As I sit in the room, where the nurse-girl is present, he calls me all manner of names. I said to him this afternoon, that, as it was too windy to go out, he had better rest an hour. 'Not in your bedroom', was his harsh reply. 'I'll rest in mother's room, but not in yours.' And tomorrow, on some trifling provocation, he would make precisely the opposite reply. He knows there is no harmony between his mother and me, and he begins to play upon the situation - carrying tales from one to the other, etc. The poor child is ill-tempered, untruthful, precociously insolent, surprisingly selfish.' (George is still talking about Gubbins, the boy child, but might as well be speaking of himself ha ha.) He ends the piece with the above quote about being Walter being 'born of a loveless marriage...'. Before the holiday, George had been referring to Walter (in letters quoted in the Diary) as 'my dear boy' - when absence had made his heart grow stronger? Had it never crossed George's mind that Walter, on being temporarily reunited with his parents and baby brother, might feel resentment at being the boy rejected and made to move out of the family home, or that a five year-old might think his parents didn't love him because, look, there was Alfred, effectively the only child now that his older brother was out the way. And what of his self esteem? Already blighted with the mole over his eye, did he feel completely unlovable because perfect babies like Alfred weren't being exiled? Children are never naughty because they are intrinsically 'bad' - they are made bad by useless, incompetent, insensitive adults.

|

| Gubbins the Fountain Cherub by Piero da Vinci (father of Leo) |

Walter was an independent-minded soul who rebelled whenever he could and gave a good account of himself in combating the 'children should be seen and not heard' mind-set. We read George's account of Walter being upset over the 'cow with the crumpled horn' story (identifying with a similarly blighted creature?) so this shows empathy. He was fussy about his clothes, which may have been a sign of over-enthusiastic and insensitive potty-training. Both Walter and Alfred suffered from urinary tract infections in their young years, which may have been caused by problems with potty habits or the wrong sort of sympathetic approach to nocturnal enuresis. (Of course, a Freudian might term fastidious attention to clean clothing as an 'anal retentive' trait.) He liked cake. He was possibly a victim of physical abuse from his mother, and it seems he could be a bit of a bully to his schoolmates (as is so often the case with abused children) - or maybe he just liked a good ruck. He was not much loved as a child, being, as he was, used as a weapon by both parents in their internecine war of attrition. The mind boggls at the pressure he was under - from all sides. The constant criticism and tellings off; the being made to feel bad; the baffling rejection; the love that did not come through the pipeline; the fear of abandonment that must have carried forward to adulthood; the feelings of inferiority; of being constantly judged; of being unlovable. Nowadays, Walter would be classified as a victim of child abuse, pure and simple. A social worker would have kept an eye on the situation and recommended a range of interventions - including parenting classes for George and Edith. Emotional abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse and neglect are now offences - Walter could claim 2 out of those 4. Alfred's might have been 3.

From the time of Walter's exile in Wakefield - after his father kidnapped him and took him without his mother's knowledge (today George would have been jailed for it - another offence, but biographers let him off all charges. If Edith - or any woman - had done it, she would have ended up in the dock), there are letters to the boy, not very naturally affectionate, smacking of duty rather than a close bond being lived. Guilt seems to have been a prime motive - guilt at having brought the boy into the world? Maybe George couldn't forgive Walter for being Edith's child. Was it really in Walter's interests to stay with the Gissing sisters and their child-beating mother in Wakefield? And, knowing his own mother's liking for corporal punishment, why did George make such an issue of Edith beating the child? Perhaps the answer to all the 'why did he do it to Walter?' questions can be answered with this: in a letter of April 1891, sent from Wakefield to Algernon, he writes 'The little lad will remain here, and be taught in the girls' school... His home has become utterly impossible. You cannot allow a hot-tempered child to grow up in an atmosphere of sordid quarrel; it would be monstrous injustice. Had not this opportunity luckily offered, I would have sent him to strangers. I will not allow him to hear perpetual vilification of his father and all his father's relatives and friends - vilification utterly undeserved in each and every quarter'. Even in and amongst George's standard lack of insight - or standard unwillingness to take the rap for his misdemeanours - here we see him blaming Edith for everything, punishing her and Walter with the ultimate sanction of the child being dragged from his home, his brother and his mother. And why? Because George resented Edith's complaints and arguments. He mentions 'vilification' twice, so that was the issue; whatever was best for the boy - and we know children thrive even in the most dysfunctional families and that siblings are best-served by being kept together - was irrelevant; George, as ever, went for what was best for himself. Cruel, hard-hearted, selfish, vengeful - yes: but, heroic? Not by a mile.

|

| Zeus and Thetis by Ingres. |

Of course, Walter was too much for his incompetent Wakefield aunts and grandma, who could not manage his behaviour, or give him the love he so desperately needed. They eventually rejected him and passed him on. Even these two women with such stunted, parochial lives must have realised Walter's unacceptable behaviour was little more than a cry for help from an emotionally disturbed child with cripplingly low self-esteem who was desperate to be wanted. Or were these two school teachers too immersed in fretting over their eldest brother? Or so focused on translating their Greek tragedies to notice the English one unfolding beneath their toffee noses? Luckily, Walter was sent to a school that could offer him structure in a nurturing environment with opportunities to shine and rebuild himself with emotional bricks - and for some sort of 'normal' life amongst 'normal' people. He continued to be shoved from pillar to post for holidays, but he survived the war that had been his childhood. Despite the loveless family upbringing, as an adult he seems to have kept in touch and on good terms with the Wakefield (later Leeds) group. He does not seem to have been the sort to bear a grudge.

It's all the more amazing that George ever considered himself a critic of contemporary mores and a commentator on children's education - areas he wrote about - after he failed spectacularly with his own children. He actively did not want either boy to read much or study and get to university - why? Would that have been unbearable to the ego of the man who screwed up his own chances at a degree? Did he think both boys being born of a defective mother would not account themselves well, academically? Being born of a defective father probably never crossed his mind. If he truly believed being educated in Greek and the Arts made him 'aristocratic' - why did George deny that to his sons? He might say what he liked about Demos, the working classes are usually in favour of their children 'bettering' themselves with education. And, despite all that stuff about Comte and the likes of Fred Harrison modelling how to raise boys, George still failed to be an honourable father. Heroism begins at home, much as charity does, after all.

|

| Demos, hoping their children might get a better life. |

|

| The Kiss by Rodin. A version of the more famous piece. |

Walter, I feel sure, liked Art. What sort of thing, we don't know, but with his love of Nature and his rebellious streak, and I suspect a disdain for convention, I have chosen some British Art he might have enjoyed had he lived beyond the First World War.

|

| Cat by Gwen John 1904/5 |

|

| Swanage by Augustus John undated |

|

| Nude by Wyndham Lewis 1919 |

|

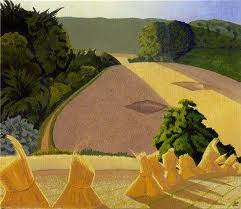

| Cornfield by John Nash 1918 |

|

| The Arrival by Christopher RW Nevinson 1914 |

|

| Merry-Go-Round by Mark Gertler 1916 |

|

| Abstract Composition by Jessica Dismorr 1915 |

|

| Wrestlers by Henri Gaudier-Brzeska 1913 |

No comments:

Post a Comment