Commonplace 204 George & Forster's Life.

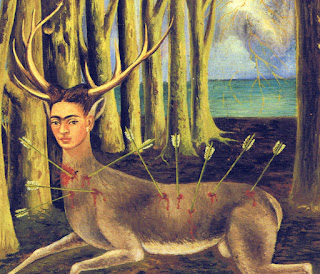

With paintings by Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723-1792).

If he is remembered for anything, John Forster (1812-1876) will forever be thought of as the man who knew Charles Dickens well enough personally to write a three volume book about his life and works: 'The Life of Dickens' (first vol pub 1872; last in 1874). Forster knew Dickens as a good friend and intimate; they were close enough for the author to appoint him his literary executor. And no one was better placed to know about the works as Dickens as he ran all his novels and part-works past Forster before he sent them for publication.

All reasonably well-educated and reasonably affluent households will have kept a copy of Forster's on their shelves, and George was very familiar with it when he was asked by publishers Chapman Hall to abridge and update it. The original three volume edition needed trimming to make it marketable in a world (1901) when Dickens was not all the rage for readers. 1901, remember, was the same year of Freud's 'Psychopathology of Everyday Life', Chekhov's 'The Three Sisters' was first performed and Booker T Washington's 'Up From Slavery' was carving a furrow through racist bigotry to demonstrate how all people, whatever their origins, have potential that cries out to be realised. Not exactly a world a-trembling for another trawl through Dickens, but there you have it.

There is an old saying: You can judge a person by the company they keep. Forster, being an all-round wordsmith by calling, mixed with literary legends such as Thomas Carlyle and Robert Browning. A particularly close associate for a time was Edward Bulwer-Lytton, 1st Baron Lytton (1803-73), a man addicted to philandering, sodomy and wife-beating, who turned to Forster in his hour of matrimonial need to get his unbiddable wife carted off to a mental asylum. John Forster was the ideal helpmate in this endeavour because, from 1861-1872, he was the Commissioner for Lunacy, having previously been the secretary to the Lunacy Commission since 1855. To understand how this governmental role oversaw the lives of the mentally ill, you can do no better than to look up 'Inconvenient People, Lunacy, Liberty and The Mad-Doctors In Victorian England' (2012) by Sarah Wise.

The Lunacy Commission was formed in 1845 to oversee the treatment and incarceration of people with mental health difficulties in a range of residential settings. I am making that sound too twee - the Commission oversaw the various levels of privately-run and publicly-owned asylums, following a series of scandals involving sexual and physical abuse of mentally ill inmates, and a trend in certifying sane, uncooperative, mostly female, family members who needed removing from the scene for financial or other reasons. In 1839, Bulwer-Lytton asked Forster to spy on his wife, Rosina, who was a problem he needed to fix. B-L was a successful author, with a vast fortune accrued from his writing, and an MP for a 'rotten borough', which was a small constituency that could be bought out or manipulated into voting for the candidate. At home, he was a cruel and violent tyrant - he kicked her in the side when she was eight months pregnant; he tried to stab her; he bit her deeply in the cheek. At the last of these, he needed to be retrained by the servants. He fled to the Continent and wrote a letter of apology that Rosina kept for future evidence should she need to move against him.

He subsequently denied both the attack and writing the letter, but as the latter was still in Rosina's possession, she had the upper hand. Bulwer-Lytton's many infidelities were common knowledge, but when she flirted with a man at a party, her husband had slammed her face into a stone floor. More damning was Rosina's claim that he had sodomised her and made her submit to a raft of sexual activities she did not want to participate in - all grounds for a successful divorce petition. Rosina was the originator of the saying ' Marriage is Saturnalia for men, and tyranny for women'. Divorce seemed the only option, but only if Rosina confessed to infidelity - which she strongly denied. A financial settlement that was well under what she could have demanded gave her freedom, and she got to keep her children.

Rosina made a significant income from her own writing - she always claimed to be the guiding light behind Bulwer-Lytton's literary success, and she had a fluid, lively style. They spatted via published verse, and he did his best to suppress publication and distribution of her works. Read her 'Blighted Lives' to find out how much she suffered at the hand of a man who refused to accept he was a monster. She was living in Bath, the watering place beloved of all the top toffs, when Forster was recruited to surveil her and report back with enough evidence to discredit her. She had just published her novel, 'Cheveley, or The Man of Honour', a satirical look at married life between aristocrats that was generally taken to be about her own marriage, and if Bulwer-Lytton could prove she was a reprobate he could divorce her, or label her as mad if evidence could be found to link her to heavy drinking. Anyone with a modicum of knowledge of George's attempt to do something similar with his first wife Marianne aka Nell, will hear bells ringing. See Commonplaces 35, 36 and 37 for more on this egregious bit of vileness from our man.

Forster didn't find much to report back about (ditto the detective George hired to surveil his wife), but advised B-L that his best course of action was to find enough for a committal under the Lunacy Act.

In fact, Forster had a good deal of animosity for Rosina as he blamed her for breaking up his marriage prospects with a young woman he fancied - so he can hardly have approached the subject with anything like an open mind. Forster later distanced himself from the matter and denied he ever suggested a committal, but there is a letter extant that puts him right in the frame. Rosina had been creating merry hell by sabotaging the hustings her husband was conducting. She turned up dressed to the nines berating her husband and encouraging the onlookers to ask awkward questions, causing the Baron to run for his life and be forever labelled a chicken. Forster colluded with Lord Shaftesbury to have Rosina forcibly taken to an asylum and detained, even though the necessary legal checks should have stopped this. In a letter to B-L, Forster writes, vis-a-vis the hustings stunt that she had spoken to the crowd in a ...most violent and excited way ... her words... were those of utter insanity... Lord Shaftesbury knows I am writing this to you, and desires me to tell you that there can be only one impression as to the wretched exhibition made by this unhappy person - a full justification of yourself in any measure you may now think is right to take.

To cut a long story short, Rosina was kidnapped and incarcerated in a private asylum where she lived with the family who ran it, and eventually won her release after a tsunami of support from the general public and an investigation into the circumstances of her captivity. She was separated from her children and forced to live in France - though what she did to deserve that fate is unclear haha. Public opinion landed firmly against Lord Bulwer-Lytton and he never fully recovered his position in public life. We shouldn't feel too sorry for him - according to his wife he advocated incest if a daughter was attractive enough to her father.

As for George, there are echoes of the part John Forster played in the assault on Rosina in the way he set about inveigling Clara Collet and Eliza Orme into helping him when he planned to have his second wife, Edith, incarcerated in a mental hospital to get her out of his way. We only have George's version of how Edith's mental health declined, but he played a huge part in unhinging her. His cruelty to her and the way he punished then persecuted her via the children, impugned her mothering skills and eventually wound her up to the point where he claimed she lashed out and trashed a shrubbery is a pale imitation of the Bulwer-Lytton case. To find out more go to Commonplaces 62-69.

And, he may well have delved into his hero Charles Dickens' investigations into having his unwanted wife, Catherine, certified insane as he thought of her as unhappy without any interest in their children. Women not being good mothers was a common claim made against women who were in the way. George himself regarded Edith as a bad mother because she let his first son listen to music hall songs! Fortunately for Catherine, the humane and concerned Dr Thomas Harrington Tuke (of the Tuke mental health care and provision dynasty), expert in mental illness advised Dickens there was no evidence to commit her. And in the end, both Dickens and Forster turned their backs on Bulwer-Lytton, and struck him off their Christmas card lists.

With paintings by Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723-1792).

If he is remembered for anything, John Forster (1812-1876) will forever be thought of as the man who knew Charles Dickens well enough personally to write a three volume book about his life and works: 'The Life of Dickens' (first vol pub 1872; last in 1874). Forster knew Dickens as a good friend and intimate; they were close enough for the author to appoint him his literary executor. And no one was better placed to know about the works as Dickens as he ran all his novels and part-works past Forster before he sent them for publication.

|

| Self Portrait aged 17 |

There is an old saying: You can judge a person by the company they keep. Forster, being an all-round wordsmith by calling, mixed with literary legends such as Thomas Carlyle and Robert Browning. A particularly close associate for a time was Edward Bulwer-Lytton, 1st Baron Lytton (1803-73), a man addicted to philandering, sodomy and wife-beating, who turned to Forster in his hour of matrimonial need to get his unbiddable wife carted off to a mental asylum. John Forster was the ideal helpmate in this endeavour because, from 1861-1872, he was the Commissioner for Lunacy, having previously been the secretary to the Lunacy Commission since 1855. To understand how this governmental role oversaw the lives of the mentally ill, you can do no better than to look up 'Inconvenient People, Lunacy, Liberty and The Mad-Doctors In Victorian England' (2012) by Sarah Wise.

|

| Sarah Campbell 1777 |

|

| Lady Cockburn and Her Three Eldest Sons 1773 |

In fact, Forster had a good deal of animosity for Rosina as he blamed her for breaking up his marriage prospects with a young woman he fancied - so he can hardly have approached the subject with anything like an open mind. Forster later distanced himself from the matter and denied he ever suggested a committal, but there is a letter extant that puts him right in the frame. Rosina had been creating merry hell by sabotaging the hustings her husband was conducting. She turned up dressed to the nines berating her husband and encouraging the onlookers to ask awkward questions, causing the Baron to run for his life and be forever labelled a chicken. Forster colluded with Lord Shaftesbury to have Rosina forcibly taken to an asylum and detained, even though the necessary legal checks should have stopped this. In a letter to B-L, Forster writes, vis-a-vis the hustings stunt that she had spoken to the crowd in a ...most violent and excited way ... her words... were those of utter insanity... Lord Shaftesbury knows I am writing this to you, and desires me to tell you that there can be only one impression as to the wretched exhibition made by this unhappy person - a full justification of yourself in any measure you may now think is right to take.

|

| Jane, Countess of Harrington 1778 |

As for George, there are echoes of the part John Forster played in the assault on Rosina in the way he set about inveigling Clara Collet and Eliza Orme into helping him when he planned to have his second wife, Edith, incarcerated in a mental hospital to get her out of his way. We only have George's version of how Edith's mental health declined, but he played a huge part in unhinging her. His cruelty to her and the way he punished then persecuted her via the children, impugned her mothering skills and eventually wound her up to the point where he claimed she lashed out and trashed a shrubbery is a pale imitation of the Bulwer-Lytton case. To find out more go to Commonplaces 62-69.

And, he may well have delved into his hero Charles Dickens' investigations into having his unwanted wife, Catherine, certified insane as he thought of her as unhappy without any interest in their children. Women not being good mothers was a common claim made against women who were in the way. George himself regarded Edith as a bad mother because she let his first son listen to music hall songs! Fortunately for Catherine, the humane and concerned Dr Thomas Harrington Tuke (of the Tuke mental health care and provision dynasty), expert in mental illness advised Dickens there was no evidence to commit her. And in the end, both Dickens and Forster turned their backs on Bulwer-Lytton, and struck him off their Christmas card lists.