Commonplace 200 George & His Return From Exile in America PART TWO.

With images from Frida Kahlo.

When George returned from America, he had no immediate prospects and no specific plan as to how he was to earn a living. When he arrived unannounced (except for a note delivered by the boy he roped in to take a hastily-written message to his mother), he probably had limited funds. Maybe his first port of call was to borrow from his mother, who was hardly in a position to refuse and maybe this is why she was seriously underwhelmed to see him and only offered one night on the couch before he had to depart for London, Dick Whittington-like, minus the cat

click.

|

| Self Portrait With Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird 1940 |

It has been suggested George's mother considered him a very real moral threat to his sisters, as they were young children who lived at home. The girls' reputations were also at risk - George was a convicted thief, guilty of the sort of petty crime middle class people assumed was only perpetrated by the working class. When he returned to Wakefield, there was no reason to assume either of the Gissing girls would remain single in their adult lives. If prospective suitors knew about George's crime spree and prison record, the girls' marriage chances may have been adversely affected. As neither married, maybe that is what happened.

William, the second son, was working in Manchester in a bank when George came back. It's worth remembering the young man had to look for work far from his home town so as to escape anyone assuming he was as light-fingered as George. On the return, William did his best to offer George support to get him on his way to a meaningful and productive life. He was much poorer than George and had fewer options for ever earning more himself, and the chance of him ever doing what he really wanted with his life - he loved music - was negligible. In a letter to George dated October 29th 1876, he writes about his wages and expenses. With echoes of Dickens' Mr Micawber, William tells his brother that there he experiences a fiscal deficit every month amounting to 5 shillings and fourpence (which presumably their mother had to make up). This left nothing for treats or buying books - George would never have settled for that!

|

| Self Portrait as a Tehuana 1943 |

What William could give for free was advice and guidance, of the sort an older brother usually gives a younger; but the boot was on the other foot, because William was the more mature of the two. Without a father to guide them, they were left to their own character-forming moral devices, and William knew George was incapable of admitting he was wrong about how to lead his life. He had wobbled off the righteous path, and William stepped in to raise his awareness of other ways life could be lived.

|

| The Two Fridas 1939 |

William was a pragmatist at heart man who summoned up reserves of determination and self-discipline to get the most out of his limited options. He was devoid of self-pity, at least in the published letters we have on record. (How different he was from George!) When he discovered the work of Samuel Smiles, William shared it with his older brother, probably knowing full well George would never be humble enough to listen to a Scottish author who recommended a life of thrift and self-control as a way to happiness. William read a few of Smiles' books, including

'Self-Help; with Illustrations of Character and

Conduct', published in 1859. Some of it will have chimed with the way the young bank clerk was forced to lead his life, but he was able to critique the book and see its limitations. Who knows what George's health, life and career would have been if only he had the humility to seek guidance from someone who was not an ancient Greek poet or a Classicist, but a doctor of medicine.

Smiles was also a reforming politician to the left of centre, who advocated change in political systems to incorporate the needs and aptitudes of ordinary people. In 1845 he had delivered a speech on the educating of the masses, something George claimed to be interested in. Here is a flavour, lifted from this source click:

I would not have any one here think that, because I have mentioned

individuals who have raised themselves by self-education from poverty to social

eminence, and even wealth, these are the chief marks to be aimed at. That would

be a great fallacy. Knowledge is of itself one of the highest

enjoyments. The ignorant man passes through the world dead to all pleasures,

save those of the senses ... Every human being has a great mission to

perform, noble faculties to cultivate, a vast destiny to accomplish. He should

have the means of education, and of exerting freely all the powers of his

godlike nature. (And of the ignorant woman?)

|

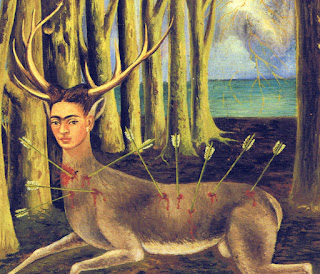

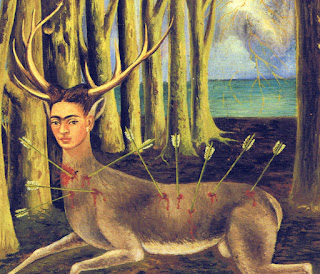

| Wounded Deer 1946 |

One of Smiles' basic beliefs was that poverty is often caused by

habitual improvidence. George was often guilty of this as he had trouble prioritising his resources, spending improvidently on expensive books, bookcases, writing desks and chairs, cushions... and tobacco whilst pleading poverty and forcing his first wife to eat lentils and dried food.

The message George might have gleaned from Self-Help was that people often abdicate responsibility for their own predicaments and could improve their prospects by self-discipline and application of principles of what we now term 'mindfulness'. In this he differed widely from the sort of tosh George was reading, especially the works of Schopenhauer who more or less put forth the idea, in a distortion of Buddhism, that struggle is pointless as we are all doomed. If nothing else, Smiles was an advocate of optimism, that thing George so despised. However, this might have touched a nerve:

Labour is toilsome and its gains are slow. Some

people determine to live by the labour of others, and from the moment they

arrive at that decision, become the enemies of society. It is not often that

distress drives men to crime. In nine cases out of ten, it is choice not

necessity. Moral cowardice is exhibited as much in public as in private life.

William encouraged George with his writing projects and never ceased to be a rock on which George could stand. In October 1877, he wrote to reassure his brother that, in time of need, Anything however small which I can ever do shall never be withheld. It might have been a different long-term outcome for William if he hadn't had to find for himself living miles from home; the daily grind of the bank with its very long hours, the travel to work in all kinds of polluted air, the dreadful cold over winter, and William's poverty must have contributed to the decline in his health. He talked about trying for a place near Wakefield (possibly Leeds) in order to make his circumstances a little easier. Perhaps he had a premonition that he would need his family's physical support as he was already doomed to an early death. Eventually, illness forced him to leave the bank and he tried to make his way as a music teacher. Towards his end, William kept away from Wakefield because he was still thinking of a life as a music teacher; his eternal optimism kept the true seriousness of his illness an unknown quantity. He died suddenly of pulmonary embolism at his lodgings in Wilmslow with his mother in attendance, on April 16th 1880. George did not attend his funeral - we should presume because he was too grief-stricken. In losing Will, he had lost his main supporter and the one person who might have helped him with advice worth listening to - someone who knew him well enough to cut through the bullshit George threw out.

|

| Me and My Parrots 1941 |

William was especially fond of George's wife, Marianne aka Nell, who seems to have been fond of him in return. Their relationship flies in the face of all those biographers who insist she was an alcoholic reformed whore, and yet claim that William was a prudish reactionary. Would such a man have befriended such a woman when the good name of the Gissings was already in the dirt? See Commonplaces 109 and 110 for more on the very likeable William Gissing.

No comments:

Post a Comment