Commonplace 126 George & The Influence of Fyodor Dostoevsky. PART TWO.

George had doings with the Russians in 1880 when he wrote articles explaining English political and cultural life for the monthly periodical Vyestnik Evropy click. He was immensely proud of having received correspondence from Ivan Turgenev click who wrote to confirm his position. George considered himself to be at home amongst the Russian greats, and this was probably why he accepted the offer and lowered his standards and temporarily discarded his snobbish tendencies towards journalism. This from the Turgenev Wikipedia page click gives an idea of what George might have gleaned from reading his work, which is quintessential George (if you substitute 'Russian reader' for 'British reader'):

"The conscious use of art for ends extraneous to itself was detestable to him... He knew that the Russian reader wanted to be told what to believe and how to live, expected to be provided with clearly contrasted values, clearly distinguishable heroes and villains.... Turgenev remained cautious and sceptical; the reader is left in suspense, in a state of doubt: problems are raised, and for the most part left unanswered" – Isaiah Berlin, Lecture on Fathers and Children.

George would have relied on translations of Turgenev's and Dostoevsky's work, and some of these might have been in German or French, both languages in which George was more than competent. English translations filtered through to the British reading public - the first of Dostoevsky's novels, 'Poor Folk', was written in 1845, but was not published in English until the 1894 translation by Lana Milman (and published in the Yellow Book with illustrations by Aubrey Beardsley click). What makes 'Poor Folk' of interest to George enthusiasts is that it is about the life of poor people, their relationship with rich people, and poverty in general... Which sounds familiar. Did George read it in German? We know he preferred both Turgenev and Dostoevsky to Tolstoy (he never forgave him for siding with the peasants!) and went to see a play version of 'Crime and Punishment' in October 1888 which he did not rate highly.

Reader, cast your mind back to those 'slum' novels George wrote when he was a rising star in the English-speaking literary firmament; Workers In The Dawn and The Nether World... and then read on.

Fyodor Dostoevsky wrote 'The Beggar Boy at Christ's Christmas Tree' story in 1876 . It was first published in his 'The Writer's Diary', a periodical he set up that ran from 1873-1881. You can read the story for free here in this publication - The St Petersburg Times click. No, not the Russian city, the Florida USA city. If you do, you might experience a sense of deja vu - because it has a flavour of 'Workers In The Dawn' and all the 'slum' novels George wrote before he came to realise he might not be the only one to have a liking for Russian novelists, and so might be taken for a plagiarist. Consider this, from the Christmas Tree story: a poor boy who lives in abject poverty with his dead parent sparked out on a thin mattress on the floor when it's so cold 'steam' comes out of his little orphan's mouth...? Arthur Golding from 'Workers'? One of Mr Woodstock's tenants in 'The Unclassed'?

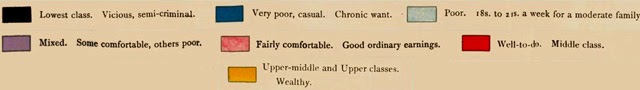

The litany of abused children in 'heaven' - something similar is the central theme of George's short story 'A Parent's Feelings'. This is one of George's most misanthropic tales, and is worth looking at more closely. You can read it here in this legendary resource: click. The Boundary Lane mentioned in the story is under the black dotted horizontal line on the Charles Booth map of 1898 click.

The story is the tragic tale of a woman who is guilty of maltreating her children, though in the times in which she lived, violence to children was considered a legitimate form of training. Just as it is nowadays amongst the less than enlightened. If you didn't know better, you might think child cruelty was/is rife amongst the working classes and absent in those deemed socially higher. This is not so. Abuse of children knows no social or cultural barrier, and middle class children were/are just as likely to be beaten and abused as their poorer peers. George's own mother was fond of violence towards her children - and any child who challenged her authority. Henry Hick (one of George's few childhood friends) tells of a child she locked in a cupboard as a punishment. By his own admission, George was a difficult child, and so no doubt felt the force of his mother's training. And George's own son, Walter, tried the patience of the two Gissing sisters'e, so they no doubt used the cane on him when they felt that to spare it was to spoil him. This 'Spare the rod and spoil the child' attitude is such a quintessentially Victorian phrase (just as is 'children should be seen and not heard') that we tend to assume everyone was making use of it. Today, we have an equally abusive and odious concept to childhood behaviour modification in the concept of the 'naughty step'. Only a moron would use this approach, but I suppose morons are as fertile as us smart folks, so I shouldn't be surprised. Anyone using either violence (physical assault) or Time Out/naughty step (emotional assault) or any form of punishment on a child needs to have a quiet word with themselves about power and its abuses, and then take themselves here click to learn about positive reinforcement (rewarding accepted behaviour) vs negative reinforcement (punishment for unaccepted behaviour), and then spend a minute or two remembering what it felt like to be a powerless child.

The eponymous parent in George's tale is not afraid to break her daughter's nose and spoil her chances of finding a good living or a good marriage just to make her abusive point. George tells us: In Boundary Lane, the 'rod was represented by a broom-handle, an old shoe, a rope-end, a fragment of firewood; in flagrant cases, perchance by the poker. This vile woman has probably killed at least one of her six dead children by over-zealous application of this sort of admonishment. The very short story is about how the child, Sue, is regularly beaten by her mother, and, as a consequence, develops anti-social tendencies that manifest themselves at school. One day, she is punished for her wrong-doing by a teacher who canes her hands as a punishment. Sue rushes home and tells her mother and the mother - well, she is outraged. Someone has dared to beat her child! What a cheek! Beating a child is the privilege of parents, not teachers... Sue's mother vows revenge on the teacher. Now, this might seem like an old-fashioned sort of tale that exaggerates its point, but how many teachers live in fear of parents coming to school to seek revenge for their told-off children? click to read more.

George doesn't introduce any mitigating circumstances to his story, or anything like an explanation for the mother's behaviour, or any sort of clue as to what might make her 'tick'. For George, her vileness is symptomatic of her base class origins. This failure to find a psychological rationale for behaviour is where he and Dostoevsky part company. What makes Dostoevsky so compelling is that he delves deeply into things like psychology, morality, motivation, and gives characters rationales that are always convincing and reasonable - even when murder is the plan. Raskolnikov in 'Crime and Punishment', is the most obvious of his creations click to be behaving in what seems like a reasonable and logical manner, with every twist and turn of his crackpot social theory to justify murder seeming convincing. His enemy, the policeman Ilya Petrovich represents an equal match in terms of guile and intelligence, but is really a reflective device to frame Raskolnikov's re-emerging conscience. Dostoevsky shows us that theory is all very well, but upbringing which provides a lodestar of morality wins out in the end. Raskolnikov is arrested, tried and punished, but he emerges from his sentence of exile in Siberia a much improved fellow. No such level of psychological awareness leading to a moral awakening is rewarded with salvation in George's main tale of exile (I say 'main' because many of George's stories are about exile). His pessimism would not allow Godwin Peak from 'Born in Exile' to benefit from his moral epiphany. Oddly, murder in Russia was punished with banishment for a few years; the punishment (albeit self-inflicted) for pretending to be a middle class Christian, was suicide.

'Crime and Punishment' will have been a book with which George felt some affinity. Raskolnikov rationalised his crimes to explain the murder he committed and framed his behaviour as a political act. George did something similar with his crime spree - he claimed (to Frederic Harrison et al) that he was a Robin Hood stealing small change from the rich to give to the poor. Utter tosh, of course. George stole money because he could.

Many of Fyodor Dostoevsky's works in English translations are available free at Project Gutenberg click.

George had doings with the Russians in 1880 when he wrote articles explaining English political and cultural life for the monthly periodical Vyestnik Evropy click. He was immensely proud of having received correspondence from Ivan Turgenev click who wrote to confirm his position. George considered himself to be at home amongst the Russian greats, and this was probably why he accepted the offer and lowered his standards and temporarily discarded his snobbish tendencies towards journalism. This from the Turgenev Wikipedia page click gives an idea of what George might have gleaned from reading his work, which is quintessential George (if you substitute 'Russian reader' for 'British reader'):

"The conscious use of art for ends extraneous to itself was detestable to him... He knew that the Russian reader wanted to be told what to believe and how to live, expected to be provided with clearly contrasted values, clearly distinguishable heroes and villains.... Turgenev remained cautious and sceptical; the reader is left in suspense, in a state of doubt: problems are raised, and for the most part left unanswered" – Isaiah Berlin, Lecture on Fathers and Children.

|

| Ivan Turgenev in his youth |

George would have relied on translations of Turgenev's and Dostoevsky's work, and some of these might have been in German or French, both languages in which George was more than competent. English translations filtered through to the British reading public - the first of Dostoevsky's novels, 'Poor Folk', was written in 1845, but was not published in English until the 1894 translation by Lana Milman (and published in the Yellow Book with illustrations by Aubrey Beardsley click). What makes 'Poor Folk' of interest to George enthusiasts is that it is about the life of poor people, their relationship with rich people, and poverty in general... Which sounds familiar. Did George read it in German? We know he preferred both Turgenev and Dostoevsky to Tolstoy (he never forgave him for siding with the peasants!) and went to see a play version of 'Crime and Punishment' in October 1888 which he did not rate highly.

Fyodor Dostoevsky wrote 'The Beggar Boy at Christ's Christmas Tree' story in 1876 . It was first published in his 'The Writer's Diary', a periodical he set up that ran from 1873-1881. You can read the story for free here in this publication - The St Petersburg Times click. No, not the Russian city, the Florida USA city. If you do, you might experience a sense of deja vu - because it has a flavour of 'Workers In The Dawn' and all the 'slum' novels George wrote before he came to realise he might not be the only one to have a liking for Russian novelists, and so might be taken for a plagiarist. Consider this, from the Christmas Tree story: a poor boy who lives in abject poverty with his dead parent sparked out on a thin mattress on the floor when it's so cold 'steam' comes out of his little orphan's mouth...? Arthur Golding from 'Workers'? One of Mr Woodstock's tenants in 'The Unclassed'?

The litany of abused children in 'heaven' - something similar is the central theme of George's short story 'A Parent's Feelings'. This is one of George's most misanthropic tales, and is worth looking at more closely. You can read it here in this legendary resource: click. The Boundary Lane mentioned in the story is under the black dotted horizontal line on the Charles Booth map of 1898 click.

The story is the tragic tale of a woman who is guilty of maltreating her children, though in the times in which she lived, violence to children was considered a legitimate form of training. Just as it is nowadays amongst the less than enlightened. If you didn't know better, you might think child cruelty was/is rife amongst the working classes and absent in those deemed socially higher. This is not so. Abuse of children knows no social or cultural barrier, and middle class children were/are just as likely to be beaten and abused as their poorer peers. George's own mother was fond of violence towards her children - and any child who challenged her authority. Henry Hick (one of George's few childhood friends) tells of a child she locked in a cupboard as a punishment. By his own admission, George was a difficult child, and so no doubt felt the force of his mother's training. And George's own son, Walter, tried the patience of the two Gissing sisters'e, so they no doubt used the cane on him when they felt that to spare it was to spoil him. This 'Spare the rod and spoil the child' attitude is such a quintessentially Victorian phrase (just as is 'children should be seen and not heard') that we tend to assume everyone was making use of it. Today, we have an equally abusive and odious concept to childhood behaviour modification in the concept of the 'naughty step'. Only a moron would use this approach, but I suppose morons are as fertile as us smart folks, so I shouldn't be surprised. Anyone using either violence (physical assault) or Time Out/naughty step (emotional assault) or any form of punishment on a child needs to have a quiet word with themselves about power and its abuses, and then take themselves here click to learn about positive reinforcement (rewarding accepted behaviour) vs negative reinforcement (punishment for unaccepted behaviour), and then spend a minute or two remembering what it felt like to be a powerless child.

|

| Peasant Women by Philipp Malyavin 1905 |

George doesn't introduce any mitigating circumstances to his story, or anything like an explanation for the mother's behaviour, or any sort of clue as to what might make her 'tick'. For George, her vileness is symptomatic of her base class origins. This failure to find a psychological rationale for behaviour is where he and Dostoevsky part company. What makes Dostoevsky so compelling is that he delves deeply into things like psychology, morality, motivation, and gives characters rationales that are always convincing and reasonable - even when murder is the plan. Raskolnikov in 'Crime and Punishment', is the most obvious of his creations click to be behaving in what seems like a reasonable and logical manner, with every twist and turn of his crackpot social theory to justify murder seeming convincing. His enemy, the policeman Ilya Petrovich represents an equal match in terms of guile and intelligence, but is really a reflective device to frame Raskolnikov's re-emerging conscience. Dostoevsky shows us that theory is all very well, but upbringing which provides a lodestar of morality wins out in the end. Raskolnikov is arrested, tried and punished, but he emerges from his sentence of exile in Siberia a much improved fellow. No such level of psychological awareness leading to a moral awakening is rewarded with salvation in George's main tale of exile (I say 'main' because many of George's stories are about exile). His pessimism would not allow Godwin Peak from 'Born in Exile' to benefit from his moral epiphany. Oddly, murder in Russia was punished with banishment for a few years; the punishment (albeit self-inflicted) for pretending to be a middle class Christian, was suicide.

'Crime and Punishment' will have been a book with which George felt some affinity. Raskolnikov rationalised his crimes to explain the murder he committed and framed his behaviour as a political act. George did something similar with his crime spree - he claimed (to Frederic Harrison et al) that he was a Robin Hood stealing small change from the rich to give to the poor. Utter tosh, of course. George stole money because he could.

Many of Fyodor Dostoevsky's works in English translations are available free at Project Gutenberg click.

No comments:

Post a Comment