George was always interested in drawing a very wide line between the working and the middle (and above) classes. This was partly to disguise his own humble origins (son of a shop-keeper; failed academic; gaol bird) and to maximise his loftier pretensions to being somehow 'aristocratic'. In fact, this demarcation wasn't entirely based on money or class, but on 'aesthetic sensibility' - George thought the poor have no right to power because they lack a refined, artistic soul, and the rich and educated are equally philistine. so, it is only a few who are touched with the greatness of aristocracy, in the Classical sense click, who deserve to prevail. Totally without irony or insight, George always placed himself in this elite by dint of the way he liked books and the Greeks. If you stop and ask yourself what, exactly, he brought to the 'aristocratic' party, you come up with... ? Maybe he confused the term 'aristocrat' with 'prig'.

|

| The Sexton's House by "BB" c 1907 |

1) a vote for all men over 21

2) the secret ballot

3) no property qualification to become an MP

4) payment for MPs

5) electoral districts of equal size

6) annual elections for Parliament |

| Woman With Plant by Grant Wood 1929 |

George was initially enthusiastic about the new Socialist movement that was gaining some influence in the late 1800s. Socialism - the idea of political power being in the hands of the largest part of the population - has its roots in the English Civil War of 1642-1651. It wasn't the victorious Puritans who promoted it, but their rebel factions, the Levellers click, the Diggers click and the Fifth Monarchy Men click. By the time George took it up, it was a popular trend amongst the educated and demimonde, much like the Occupy Movement is today click. And, just as with Occupy, amongst the real devotees were dilettantes and hangers-on - and George was one of these. Part of his falling out of love with the movement may have been the distinct hierarchy above him that he would not be able to challenge or overtake. The likes of William Morris were already in the best positions, and there was nowhere a little minnow like George could establish a toe-hold (or a fin-hold haha). More likely, he turned his back on joining in with any movement that would have had strong and frequent links with his old hunting ground of Manchester.

The lure of Positivism claimed George, and through his association with Frederic Harrison he found employment, some social recognition, a limited readership for his fist novel, and a smattering of knowledge about statistics. So, what is Positivism? This click explains it fully. Basically, it was a belief system that relied on accepting only empirical evidence; this means what you experience from your own sensory input is more valid than any interpretation you make of that sensory input. Current aspects of Behaviourism are close to the basic idea of Positivism. Because Positivism relied so wholeheartedly on the perspective of the individual, a system was required to establish norms of behaviour, so that human experience could be assessed and compared with what was usual in any particular social group. And so sociology was born.

|

| Cookham by Stanley Spencer 1914 |

|

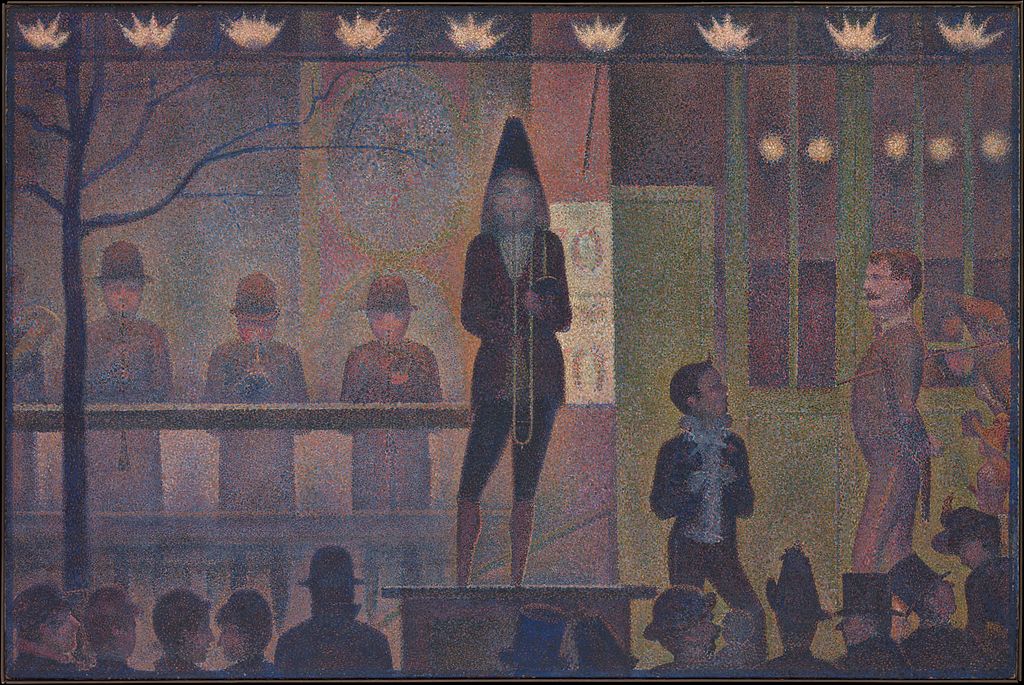

| Parade de Cirque by Georges Seurat 1887-1888

Apart from not wanting to be mistaken for a common oik, George was one of many who believed that life under the rule of Demos would be one where Art was relegated to a minority activity and that vulgarity would prevail. As Art has never been anything but a minority interest, and as the very definition of what is vulgar is the quotidian, it's difficult to know what George's problem was with either notion. But, wouldn't that have appealed to George? In fact, it would have suited him to live under a system where he could feel even more marginalised and even more of an outsider?

|

No comments:

Post a Comment